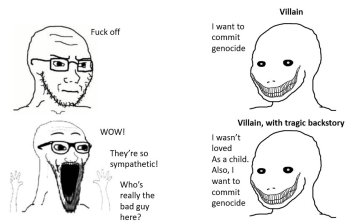

It might be an old – and somewhat uncouth – meme, but it makes the point. Slap an unhappy backstory on a villain, and odds are that someone somewhere will ask whether or not he is “really the bad guy.” How can Thanos, for example, be considered evil when he just wants to prevent other worlds from suffering his homeworld’s fate?

First, if Titan was as technologically advanced as it is supposed to have been, Thanos’ plan would have done nothing but pile up corpses. Fairly, of course – he did say he wanted it to be “at random,” something he practiced on Gamora’s and too many other worlds. I am sure that was a great comfort to those who were left behind; Gamora certainly seemed to appreciate it.

Yes, I am being sarcastic, and purposefully so. This leads to my second point: If Titan was sufficiently advanced to have space travel (which they do in the comics), then there is no way they were consuming resources at a rate that would deplete their world and cause it to die. Look no further than Star Trek* for proof of this concept – where is the concern about using up resources in the Federation? It is non-existent, because the technology they have prevents the concern that a large population would reduce Earth’s and other planets’ resources to the point that mass genocide would be “needed” to save these worlds.

Odd how Thanos seemed so concerned about Titan and not the people who called it home. Maybe that has something to do with the backstory cut from Infinity War, showed Thanos being bullied and mocked for his “freakish” or “mutant” appearance. It is a pretty standard Sad Backstory™ for villains these days, so this author did not give it much thought when she read about it first. She just rolled her eyes and moved on.

Then I heard Thanos mention his homeworld’s growing “instability” in the movie. I have no idea what others thought when they heard him use that word to describe his planet in its death throes, but it did not signal “depleting resources” to this viewer. It implied a core instability in the planet itself – i.e., Titan’s core was becoming unsteady. That would mean that no matter what anyone did or did not do, Titan was doomed to die. It was a dying world because it had reached its lifespan’s limit.

Yes, planets have a lifespan, future authors. Everything in the universe has a lifespan. Stars are born and stars die, but because they are part of the vastness of space, we here on terra firma hardly notice when this happens. Trees, flowers, and grass have lifespans. Animals, microbes, et al have a lifespan – a set time of years, days, or even hours in which to live. Once that limit is reached, the organism dies.

Titan was dying, much the way that Krypton died in DC’s comics. The planet was going to become a barren, unstable rock no matter what anyone did. Its inhabitants recognized this (or did not – we do not know for sure because our only source of information is Thanos, and he is a liar), meaning they knew there was nothing they could do other than accept their world’s demise.

Since they were a star-faring civilization, it is quite possible some of them left before Titan died. But all of this puts Thanos’ genocidal Final Solution in a new light, does it not? His world is dying an inevitable death, and he suggests murdering billions – fairly, mind you – in order to save Titan.

Yet from his own mouth we learn that there never was a solution to Titan’s death throes. The consumption of resources, fast or slow, cannot affect a planet’s core. It is impossible, since the Earth’s core never noticed when the dodo went extinct. It did not even notice when men died in the trenches of the Somme. Why would the destruction of forests in Germany or fires in Australia have the slightest bearing on the stability or instability of the center of the Earth? Answer: they do not affect it, because they have no bearing on it.

Neither do mining operations. The deeper one digs into the Earth, the hotter it gets. Yes, it gets hotter the further down one digs. Look up the TauTona Mine in South Africa, or the Kola Superdeep Borehole in Russia. Without ventilation, a human going deep into these places would die from the heat. We cannot reach the Earth’s core with our mining operations because the tools to do so do not and may never exist. We don’t have anything that can bore into the core of a planet and destabilize it, making our mining operations no more dangerous to the Earth’s stability than a piercing in a human’s navel is to that same person’s heart. It is not going to happen.

But because Thanos is “trying to do the right thing” and has “such deep humanity,” reviewers give him a pass for his evil. And yes, he is evil; anyone with a working moral compass can see his wickedness plain as day. His world was dying but he suggested saving it with mass murder. If he believed in that plan so much, then he should have led the way and killed himself first, just as he should have cast himself off the cliff on Vormir to gain the Soul Stone.

Some will inevitably trot out this piece of writing advice to “explain” his motivation: “Oh, but he thought he was the hero of his own story.” If so, then Thanos was a more masterful liar than Loki, who tried to convince himself that he could have Earth if he allied with Thanos. (No, I do not believe the MCU retcon that Loki was mind-controlled by Thanos into invading Earth. Read the comics or, better yet, the original myths. Tom Hiddleston is a great guy, but Loki is not.) Thanos knew exactly what he was doing on Titan and on other worlds. He was getting revenge for every taunt, every jibe, and every hurtful shove or comment he had endured for being born “deformed” among normal Titans.

That is not the act of a man who thinks he is a hero. That is the behavior of a man who knows his own iniquity but wants to persuade people that he is not truly bad – or that he has their best interests at heart. Remember the practiced little speech Ebony Maw gives to those Thanos murders? The one he recites aboard the Statesmen, before he is confronted on Earth by Tony Stark and Dr. Strange, then again in flashback on Gamora’s world? If not, here is a clip to refresh your memory:

Whether or not you believe in God or the divine, this speech proves that Thanos has arrogated godhood to himself. He has made himself judge, jury, and executioner. When he comes back to take the Infinity Stones in Endgame, he also attempts to make himself the Creator. But since man cannot create ex nihilo or out of nothing, to accomplish that monumental task he has to destroy the Cinematic Universe (a stand-in for our universe) first.

Overweening pride does not begin to describe the hubris Thanos must have to think he has a right to claim these powers for himself. “You will not die,” the serpent told Eve in the Garden. “You shall be as gods.” The first sin, pride, has not left us. If anything, it has grown blacker and stronger since the Fall of Adam and Eve.

It is that pride which leads people to try to excuse evil, up to and including the ridiculous sound bite writing advice that “the villain is the hero of his own story.” One cannot look at what Thanos does and intends to do in the MCU without seeing the depths of his depravity, which run directly counter to the idea that he thinks himself a hero. He emphatically states that he thinks of himself as some inverted messiah made to suffer the “misunderstandings” of the lesser beings he has come to save – without truly suffering himself on their behalf.

This reminds me of a quote from X-Men: Evolution’s* Magneto: “Unfortunately, sometimes salvation must be force-fed.” Funny how the True Savior (whether or not you believe in Him) never compelled anyone to seek salvation. Yet all His dark imitators insist that their followers must obey them to the absolute letter of the law they set down and which they themselves do not follow. Remember, Thanos believed in his plan so much, he thought others ought to die for it.

Unless the author willingly blind himself to his villain’s malice – or he secretly craves the power that the villain has, desiring it for himself – he cannot miss the corruption of his hero’s opponent. This is where we get to the “who’s really the bad guy” question, which never ceases to amaze me, since it is an asinine query with regard to a villain like Thanos. The same is true of villains like My Hero Academia’s* Shigaraki and his companions in the League of Villains. One cannot even use this piece of writing advice to excuse the actions of the sole sympathetic antagonist of MHA: Gentle Criminal.

This is where the modern world’s urge to worship evil obscures things and makes them difficult to discuss, primarily because it has neutered the vocabulary needed to do so. One can feel sorry for Thanos due to the bullying he endured; however, no one can say with a straight face that his decision to avenge himself on the universe is not wrong and deeply evil. Beyond that, his plan is also insane: no matter how he tries, man cannot become God. Loki, of all people, even tells the Mad Titan that in Infinity War. Thanos will never be a god because he is reaching once again for the forbidden fruit, which assures his failure and his fall.

As for My Hero Academia’s villains, author Kohei Horikoshi has given a number of them pitiable backstories. But as Mr. J.D. Cowan explains when discussing Stain the Hero Killer in his article here, the fact that the villains are sympathetic and may even have a valid critique of society does not excuse them for their wicked actions. Not once in the entire narrative of the manga does Horikoshi provide cover for his villains; they are unfortunate lost souls, and the hero of the story – Deku – wants to save them.

Yet even Deku admits that he may have to kill his nemesis, Tomura Shigaraki, in order to protect innocents. He wants to save him, and the heroes of the past validate that desire. But they never rescind their question: if he has to, will he be able to kill the man for whom he has compassion? They all know he may have no other choice but to kill All for One’s heir apparent. No matter how distasteful this is to them, though, they recognize that they may not be left with a choice in the matter. It is a fact which Deku understands as well, which he demonstrates when he says that while he has not figured out how to kill Shigaraki, he will do it if there is no other way to protect innocent lives and see justice done.

Tomura Shigaraki is a truly pathetic figure. He was abused first by his birth father, then by All for One, the arch-villain of the series. None of that excuses Tomura’s hatred for “everything that draws breath” and his maniacal desire to exterminate all life on Earth. It does not justify his actions in the war on heroes and the society of Japan. He can be forgiven, pitied, and understood. But he cannot be allowed to continue on his path of destruction, which means that Deku and the other heroes cannot excuse his actions. They also cannot afford to let him live if he clings to his hatred and refuses to be saved.

The rest of the League are at least somewhat sympathetic due to the circumstances that led to their villainy. But with the exception of the now-deceased Twice, they are all murderers intent on continuing to maim, torture, and kill innocents in an effort to “be themselves” and become “unshackled” from hero society. Although they have valid critiques of hero society’s system, Horikoshi never once uses these items to excuse their evil. Readers and viewers cannot – though they do, unfortunately – ask “who is the real bad guy” in My Hero Academia. The series and the author do not allow that question to be asked because the answer will always be a lie; the heroes are the heroes of the series, not the villains. Despite attempts to obfuscate this fact in the West, anyone reading the manga and/or watching the anime can see the distinction made plain before their eyes.

But, some ask, what about Gentle Criminal and his partner in crime, La Brava? The two are the most piteous of the villains introduced in MHA. They were cast out of society: Gentle tried to use his Quirk without a license to save a life, interrupting another hero’s work in the process. La Brava’s Quirk – love – affects her personality and makes her passion for a particular person spill over into near-obsession. The first time she lets feelings loose, she overhears her classmates mocking her and retreats from society.

Determined not to be forgotten, Gentle decides that if he cannot become a hero, he will become a villain instead. La Brava finds the videos of his crimes online, falls in love with him, and joins his crusade. For once, her love is returned, and Gentle takes her in with a whole heart and no reservations.

The two are petty criminals who never commit large-scale, impressive crimes and they avoid bloodshed. To a degree, one can argue that they are not bad people, which the League of Villains manifestly are. Nevertheless, the two never claim to be heroes. When they battle Deku in an attempt to enter U.A. High School (where he is training, and which is under tight security due to the League’s attacks) they fight with the passion of trying to achieve Gentle’s desire and for love of each other.

Although he sympathizes with them more keenly than they realize, Deku does not waver in his efforts to stop the two. The entire U.A. campus has been stressed to the breaking point and are currently having a “School Festival” to unwind and relax. Moreover, the staff and Class 1-A have taken in an abused girl – Eri – who no longer remembers how to smile. This event is something that Deku and others close to Eri hope will help her begin to recover from her psychological and physical abuse.

So like Gentle and La Brava, Deku has very good, powerful reasons to refuse to let them in to U.A. And that passion, because it is ordered to something right and just, is what allows him to win. He does not stop empathizing with the couple or insist that they are evil; he only insists that they have no right to take Eri’s potential happiness from her, or the happiness of the rest of the students who have been thrown into adult situations so often they need a break.

This is why Deku is the hero of the story while Gentle Criminal and La Brava are villains. They are sympathetic villains, and there are hints given that they may be redeemed in the future. But no one ever tells Deku he was wrong to stop them – in fact, his work is validated after the festival by none other than the little girl he fought so hard to save. Eri rewards Deku’s efforts with the biggest, happiest smile a girl her age who has been through so much trauma can produce.

“The villain is the hero of his own story”? No, he is not. He may try to tell the protagonist or the hero that he is the champion of his own adventure. He may also try to convince himself that he is the hero of his own tale.

But that will be a lie, one the author at least should see through, if the characters cannot or will not. The bad guy is always the bad guy because he wants to be so. He can stop and turn aside at any time if he chooses. If he chooses to remain on his trajectory of wickedness, however, the author cannot – and most emphatically should not – defend his decision.

Remember this, future writers, and you will have memorable villains your audience will be talking about for years. The greatest writers never excused the bad guys’ actions, desires, or lies and it never hurt them in the slightest. Why, therefore, would it hurt you to be honest about “who is the real bad guy” in your fiction?

If you liked this article, friend Caroline Furlong on Facebook or follow her here at www.carolinefurlong.wordpress.com. Her stories have been published in Cirsova’s Summer Special and Unbound III: Goodbye, Earth, while her poetry appeared in Organic Ink, Vol. 2. She has also had stories published in Planetary Anthologies Luna, Uranus, and Sol. Another story was released in Cirsova Magazine’s Summer Issue in 2020, and she recently had a story published in Storyhack Magazine’s 7th Issue and Cirsova Magazine’s 2021 Summer Issue. Order them today!

These are Amazon affiliate links. When you purchase something through them, this author receives a commission from Amazon at no extra charge to you, the buyer.

Like Caroline’s content? Then consider buying her a coffee on Ko-fi to let her know you appreciate her work. 😉

This is one of the things that has kept me pissed off almost continuously about a number of recent stories. Sometimes, the “villain” is just somebody trying their best in a crazy, insane world that eats away at them. They make bad decisions. They make bad choices, and don’t know how to get out. And, if they’re given a chance to get out, they just might take it.

But, more often than not, the villain is dangerous. You can sympathize for them, you can feel sorry for them, you can regret what you have to do. But, you have to stop them. Because they have crossed that line into monstrous acts and they must be stopped. And, stopping them would probably require them to be killed.

Villainy also has this “simplistic teenage rebellion” aspect to it. Often the villains are an act of a dilettante-a simple solution to a complex problem. Or sheer egotism-it’s all about them, and what they want, all the time.

And, for some damned reason, that is attractive to far too many people.

(I know the reasons, several of them. Especially for women with “bad boys,” but that’s a whole Venn diagram discussion.)

The trick, which a lot of writers don’t really pull off as well as they should, is to make a villain sympathetic but still needing to be stopped utterly. And to make the heroes hate having to do it-but knowing that the job has to be done anyways.

LikeLiked by 2 people

Recent fiction is really bad about this, I agree. Some villains in certain stories may be lost souls making bad choices trying to do good things, but many villains across genres are outright evil and can only be stopped by the expedient of making sure they cannot come back. The hero can regret this necessity along with the audience and even wish he didn’t have to do it – that does not make him less of a hero. In fact, it makes him a better hero. But that doesn’t change the fact that some villains just have to be taken out for everyone’s safety going forward.

You are right to say that, more often than not, the monstrous type of bad guys are really beyond saving. The ones that can be talked down, shown the right path, etc. – they’re looking for a way out of their cycle of bad choices. They may not realize it all the time, but that is what they are doing, and that means they can be rescued. Others, though, have willingly crossed the line into purely evil acts and they have no intention of going back. There is only one way to stop them, no matter how much the hero wishes he didn’t have to do it, and writers need to recognize that more than they have lately.

I’ve noticed the “dillettante” and “teenage rebellion” villains, too, though the “sheer egotism” motivation is not used obviously very often (Thanos is the most blatant example in recent media). Shigaraki fits these criteria, especially early on in My Hero Academia. It works as a motivation, and it can be used to help the audience sympathize with him while realizing at the same time that there may be only one way to stop him. Horikoshi is one of the few modern writers to do that well, though Western critics refuse to see that, preferring to excuse his villainous behavior instead. But that isn’t the point of his arc, and I wish more people would at least talk about that. Sigh…

LikeLiked by 2 people

Recent fiction is written and/or edited by people that have grown up with the idea that there is no such thing as “evil” (outside of Catholic religions, certain political and racial types that have not done penance, and a few other categories). It’s all “perception” and “if he’s pretty, he’s not evil/can be redeemed” and a lot of other things that make you lose hope sometimes…

Look, I like a good villain. Spike was always fun to watch, especially in the last few seasons of BvS and Angel, where he had to figure out who and what he was. Zuko was a great redemption story arc and he worked his passage to the fullest. You need a good villain, to contrast the heroes and their struggles.

But, they were still villains. They still had to work their passage to be redeemed-and you could see it in action. And, there were far more absolute villains and monsters. Often they were the same thing…but not very often.

In my more worried/creepy phase, it is because the writers and creators think that the villains are on the losing side, not the wrong side. That the “heroes” are that just because they have better press. That the “heroes” are the worst villains because of their better press, because they are hiding systemic injustices and atrocities. That they’re fools for allowing it to happen-or they’re helping it to happen for whatever reason.

It’s tiring. It’s frustrating. It’s childish. And, most importantly, it’s boring.

LikeLiked by 1 person

The thing that I hate about the Thanos in those movies is that In The Comics he kills because he’s in love with the Persona Of Death (in the Marvel comic universe).

So yes, the Movies tried to take an out-and-out Evil Villain and make him “sympathetic”.

Nonsense.

I can understand the idea that the Villain may need to be given reasons for his Evil (not doing things because they’re Evil Things) but you should never Excuse the Evil.

Yes, the Magneto who is a Nazi Death Camp Survivor is a Better Villain due to his motivation to prevent another Holocaust (with Mutants in the place of Jews) but he is still an Evil Would-Be Dictator.

There are plenty of reasons to see Magneto as an Evil SOB.

You shouldn’t Excuse Magneto’s Evil because he’s a Nazi Death Camp Survivor.

LikeLiked by 2 people

Agreed on all points. While the film version of Thanos’ modus operandi has its uses in making a variety of points, his original, comic book motivation is much better than the one within the movies. I mean, he’s a man obsessed with the female personification of death! Don’t tell me a competent screenwriter couldn’t have made a good movie or even a two-parter film about that. Sigh…

You’re right about Magneto as well; he is a better bad guy for being a Holocaust survivor who wants to prevent history from repeating itself, but part of his function is to show how he is making history repeat itself. He is the very thing he swore to destroy and hates with such passion, but he won’t admit it. So a viewer can feel sorry for him, even sympathize with his concerns. But that doesn’t change the fact that Magneto must be stopped at any and all costs. Even Professor X acknowledges that, having gone to great lengths to stop him (if not kill him) in the past. And he is, arguably, the person who wants to save Magneto most.

The Master of Magnetism’s past is used a lot to give him a pass, which shouldn’t happen and was never intended by the writers. It is a shame. Magneto deserves better than that.

LikeLiked by 1 person

I always liked Grant Morrison’s take on Magneto-“No matter how he justifies his stupid, brutal behavior, or how anyone else tries to justify it, in the end he’s just an old bastard with daft, old ideas based on violence and coercion…”

And, that’s how you write a villain like him proper.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Hear, hear! An excellent point! Thank you for bringing that quote to the table, Author In Charge. I might just use it in a future piece somewhere down the line! 😃

LikeLiked by 1 person

Once you empathize with the villain, your choices are denying that he’s a villain, or admitting that you have villainous elements in you.

Which is easier to accept?

LikeLiked by 2 people

Well, I KNOW that I have villainous elements in me.

LikeLiked by 1 person